I just came across a 1955 Superman story called 'The Girl Who Didn't Believe in Superman'.

I just came across a 1955 Superman story called 'The Girl Who Didn't Believe in Superman'. I think I first read it in a British Superman Annual when I was a kid. I can't think why I, a devout Marvelite, allowed such a book into my bedroom. Re-reading it makes me wonder if there is after all a precedent for identifying the Last Son of Krypton with the Son of God.

The Daily Planet is organizing it's annual 'Lovely Child' photo competition. The prize is a round-the-world sightseeing tour with Superman: but the winner of the competition, little Alice Norton, turns out to be blind. Not only that -- but she doesn't believe that there is any such person as Superman. The Man of Steel uses his super deus ex machina power to become an accomplished eye-surgeon and performs an operation which restores Alice's sight. She realizes that Superman is real after all, and he takes her on the promised world tour. Because of the publicity, Alice's long-lost father turns up: he's been in hiding because he blames himself for the road accident which blinded her. His wife reveals that he wasn't really to blame. Superman has not only restored her eyesight and her joie de vivre, but also Alice's family.

The splash-page for the episode shows Superman dragging a truck through the street on a chain to demonstrate his super-strength. Alice stands to one side saying "It's all a trick. There is no such person as Superman." This idea is elaborated in the first section of the story: Superman demonstrates his various powers to Alice, but she provides a rational explanation for each of them. (For example, when he uses his telescopic vision to tell her what her mother is doing she replies, not unreasonably, that it's common knowledge that she works as a child-minder in the afternoons.)

This is a modern take on the old story about the blind men and the elephant. It amusingly shows how someone's beliefs about the world are determined by their point of view. It is also a classic Superman puzzle story. The young reader is supposed to be amused by the ingenuity of Alice's rationalizations, and to wrack his brain to think of a super-stunt that she can't explain away. (Much of the 1950s was spent pitting Superman against deliberately un-super opponents. "How can I convince a blind girl that I am Superman?" is really the same kind of question as "How can I trick Mr. Mxyzptlk into pronouncing his name backwards?") The resolution to the puzzle – that Superman's X-Ray vision accidentally reveals the cause of Alice's blindness – is actually a bit of a cop-out. But it takes the story off in a new and much more interesting direction.

Alice's real problem is not her blindness: it's that she is caught up in a post-modernist paradox. She thinks that Superman is "a myth, make believe, a modern fairy tale." She tells the Man of Steel that "No man could have super-powers like that! Superman is just make believe...like the fairy tales Mommy tells me!" But from our point of view, that is precisely what Superman is: a modern fairy tale. The imaginary Superman-free world that Alice has created for herself is the same as ordinary world which we readers live in every day. Alice's mother say that "she retreats from reality more and more each day" – even though for us, it's believing in Superman, not doubting him, that would be considered a retreat from reality.

Alan Moore's classic 1986 story "Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow" began with the brilliant line "This is an Imaginary Story. Aren't they all?" I think that Bill Finger had made the same joke 30 years previously.

Alice's physical blindness is a metaphor for her inability to perceive the innate goodness in the world. According to her mother "Because of her blindness, Alice has become a bitter, cynical child!" This cynicism is explicitly connected to her disbelief in Superman. "She must be drawn out of her shell! She must be made to believe in life again! If I can make Alice believe in me, she might begin to believe in the world around her...in the pleasure even a blind child can have! That's why it's so important that I convince her there is a Superman!" It's her skepticism, not her disability, which is the problem: if she believed in Superman then she could enjoy life – even if she remained blind.

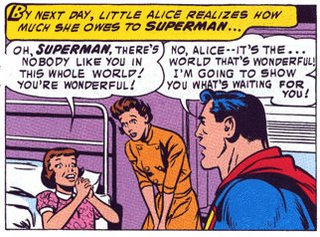

Having restored her sight, Superman flies Alice around the world. This is not depicted merely in terms of a person who has suffered a temporary loss of vision enjoying their restored faculties: we are supposed to imagine someone seeing the world for the first time – indeed, discovering for the first time what kind of world they live in. "This is your country" says Superman. "Golly! I never realized America was so big!" she replies. The word "wonder" is used four times in this sequence: Alice says that Superman is wonderful for having healed her; Superman says that it is the world itself that is wonderful. And Alice, who a few pages before was being cynical about fairy tales, suddenly decides that the whole world is like children's fantasy and she is a character in it. "It's just like you said it was...wonderful! Alice in wonderland, that's me!" Bet you didn't spot that line coming. The restoration of Alice's physical sight is a metaphor for the restoration of her "sense of wonder".

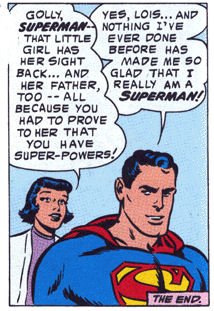

What does the story 'mean'? In 1955, comics were written by adults and read by children. (Today, they are written by fanboys and read by no-one.) The comic may be playing with the idea that adults who lose their childlike enjoyment of fantasy also stop enjoying real life. It may simply be a warning to its readers not to lose their sense of wonder. It may even be telling them, very gently, that although they will one day grow up and realize that there is no Superman, the world is still very wonderful without him. At the beginning of the story, Alice's rejection of Superman is a rejection of the world itself. When she recovers her vision, she wants to give all her attention to Superman, but he points away from himself, and toward the world. In the penultimate frame, Alice has literally turned her back on Superman, because her attention is directed to her happy family. Superman slips away without saying goodbye, leaving Alice, in a very positive sense, back in a world without Superman. "Come on" he says to Lois "They don't need us any more." The Alice of the splash page ("there's no such person as Superman") and the Alice of the last page ("they don't need us anymore") could be seen as negative and positive metaphors for growing-up.

But when I read a story about faith, which involves the healing of a blind person, I am inclined to ask whether the story is "really" about Jesus. In the Bible, Jesus heals several blind people; indeed, he begins his mission by announcing "freedom to the captives and recovery of sight to the blind." The New Testament healing stories are just that – stories about supernatural cures. But Christians also read them as metaphors about spiritual healing and forgiveness. "I once was lost, but now am found, was blind, but now I see." For a Christian, to come to believe in Jesus is to have your eyes opened; to see the world in a new way. Can this possibly have been in Bill Finger's mind when he depicted a little girl healing her life by believing in Superman?

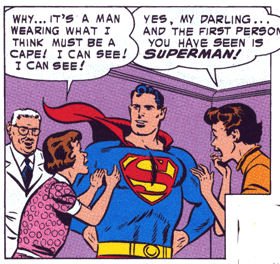

The scene in which Alice is healed is worth a close look. Superman can instantly memorize the contents of an entire medical library and uses his X-Ray vision and super-speed to perform an operation which no earthly surgeon could ever do. (This raises a question -- why doesn't he use his knowledge and power to heal all the other blind children in the world? – which some people have also wanted to ask about God.) The actual surgery isn't shown: all the drama is saved for the day when the patients bandages are removed. I don't know what post-operative dressings look like in a real hospital, but here, they look exactly like a blindfold: as powerful a way of illustrating "recovery of sight" as you could imagine. The whole sequence has a Biblical whiff. The captions drift into archaic language "Slowly, the binding cloth..." (why not just "bandage") "is unwound" (not "removed" or "taken off")"and light falls upon Alice's staring eyes!" Alice only gradually works out that what she is looking at is the Man of Steel. "Something...tall...it's getting clearer...why...it's a man wearing what I think must be a cape! I can see! I can see!" Bill Finger has temporarily forgotten that she was only blinded four years ago and knows perfectly well what a cape looks like. The metaphor about "seeing the world for the first time" has temporarily overridden the literal story about a child with a fragment of a windshield in her optic nerve. Does this recall the Biblical story of the blind man who said "I see men as trees, walking."? Many a preacher has pointed out that the first person that the blind man saw was Jesus: Alice's mother exclaims that the first person her daughter sees is Superman. In the next frame, Alice adopts what is distinctly an attitude of prayer to thank her saviour. Her words to Superman seem a bit prayer-like as well "Oh Superman! There's no-one like you in the whole world!"

The final incident in the story is also worth a glance. (Didn't they cram a lot of story into 10 pages in the 50s?) It seems that Alice's father disappeared after the road accident which originally blinded her. "I couldn't look at my little girl's sightless eyes without knowing that I was responsible because I was driving the car!" In fact the crash was caused by a mechanical fault for which he was not to blame. He's been "running away needlessly from his own conscience!" It would be over-subtle to see this as an allusion to the disciples' question to Jesus about the blind man in John's Gospel ("Rabbi, who sinned, this man or his parents, that he was born blind?") But it is very, very striking that Superman's actions have not only cured Alice of her blindness, but also cured her father – who is called John, by the way -- of his guilt. It goes without saying that for Christians, the important thing about Jesus wasn't that he cured sick people, but that he told them that their sins were forgiven. Alice's father is briefly suspected of wanting to steal the money which generous Daily Planet readers have donated to help Alice and her mother. This also represents a change in how Alice sees the world "I never realized people were so good."

For anyone who grew up with Stan Lee's melodramatic over-writing, this 1950s Superman is astonishingly simplistic; even naive. There is hardly one word of what you could call dialogue in the whole story: everyone talks in pure exposition and the "Alice in Wonderland" line made me cringe with embarrassment even when I was 10. However, like many superficially naive children's stories, it actually has considerable complexity and emotional depth. We have a character whose literal darkness is the outward representation of an inner darkness – she has no father, her mother is poor,she thinks that there is nothing nice about the world -- all summed up in her disbelief in Superman. Superman heals her, restores her inner light, her family, and makes her see things she never saw before – the beauty of America, the inherent goodness of the human race.

Any relationship between Superman and Jesus is one of resemblance rather than symbolism: Superman, the character, does some of the same kinds of things which Jesus did, with some of the same kinds of results. This seems to me to be more sophisticated and effective than the approach of the movies, which do little more than point up certain supposed similarities between the origin of Superman and religious saviour myths. I think that the religious language that is used in the "healing" scene makes it more than likely that Finger was aware of the overtones of his story. But maybe a half-remembered Sunday School lesson just worked its way onto the page while he was writing against a deadline.

Any relationship between Superman and Jesus is one of resemblance rather than symbolism: Superman, the character, does some of the same kinds of things which Jesus did, with some of the same kinds of results. This seems to me to be more sophisticated and effective than the approach of the movies, which do little more than point up certain supposed similarities between the origin of Superman and religious saviour myths. I think that the religious language that is used in the "healing" scene makes it more than likely that Finger was aware of the overtones of his story. But maybe a half-remembered Sunday School lesson just worked its way onto the page while he was writing against a deadline.

Andrew Rilstone is a writer and critic from Bristol, England.

If you have enjoyed this essay, please consider supporting Andrew on Patreon.

if you do not want to commit to paying on a monthly basis, please consider leaving a tip via Ko-Fi.

The Girl Who Didn't Believe in Superman was written by Bill Finger and drawn by Wayne Boring and Stan Kaye. Superman is copyright DC comics. All quotes and illustrations are used for the purpose of criticism under the principle of fair dealing and fair use, and remain the property of the copywriter holder.

Please do not feed the troll.

.jpeg)