i'm sorry i just couldn't resist

Friday, September 01, 2006

Davewatch

i'm sorry i just couldn't resist

Davewatchwatch

As long as we speaking in the Vulgar Tongue, I have no problem in saying that Mr. Dave Sim is crazy, cracked, loony, potty, insane, several land cards short of a Magic deck, nuttier than a fruitcake factory which is hosting the annual convention of the Cashew Appreciation Society. I have said so myself on many occasions. My only problem is with people who use 'He's mad' as shorthand for 'I can form a critical judgment about Cerebus the Aardvark without the bother of actually reading it.'

Earlier this year, Steve Bolhafner, stalwart of the Cerebus mailing list described me as:

The conflicted Andrew Rilstone who I think loves and hates Cerebus in equal proportions more strongly than almost anyone (there are those who love it more and hate it less, and vice versa, but he is very strong and articulate about both positions).

I believe that this was intended to be a flattering remark, and I took it as such. But I think that there is something a little off-the-wall about needing to describe me as 'conflicted'. I think that Cerebus is a masterpiece and Dave Sim is an idiot. What is 'conflicted' about that? 'Greatest living comic book creator and total asshole' is a sentence I am still rather proud of.

Having read Cerebus the Aardvark and the associated essays notes and letter columns and commentaries, I tend to experience Sim as a series of gobbets of total lunacy strung out like idiotic pearls on a string of interesting, creative and verbally inventive writing. People who gave up on Cerebus after Melmuth have largely experienced mad-Dave only via his most extreme and therefore most widely quoted remarks. (The Victor Reid material in Cerebus #181; 'Tangents', the bonkers interview in the Onion.) Obviously, my Davewatch thing contributed to this tendency. I don't say he doesn't believe the madstuff; but I do say that that isn't all he ever talks about.

It's a bit like discussing the Ring Cycle, the Silmarillion and the Bible. Long, inaccessible works: people who don't like them tend only to know them from a few isolated passages for the very good reason that the only people who can be bothered to encounter the complete work are those who are fairly sympathetic to it in the first place.

'So Andrew, what you are saying is 'I'm the only one round here who's slogged through Sim's writings, so I am the only one who is allowed to slag him off.' '

'You could put it like that, I suppose.'

When we go beyond this and describe Sim as mentally ill we appear to be talking about his behavior: his asceticism, his celibacy, his reclusiveness, as opposed to his gnosticism, his extreme anti-feminist theories and his alleged personal misogyny. (*) Of course, many respectable religions have a tradition of hermits and anchorites, to say nothing of vows of poverty and clerical celibacy. But I am happy to grant that cutting off your links with your family is not widely regarded as normal behavior. 'Dysfunctional', 'maladaptive' and 'unable to function in society' might be apt descriptions. This may be one of the things which is meant by 'mental illness'.

How is this 'mental illness' related to his strange theories? Without the whole case history before us, we can't know. Perhaps Dave came up with the idea YHWH was a ball of fire at the center of the earth and therefore ostracized his mother. Or perhaps it just so happened that he developed a bizarre theological theory, and quarreled with his mother at the same time. Or maybe the experience of living alone without any human contact caused him to produce these rather elegant and ingenious but entirely self-referential religious models.

The commentary on 'The Last Day' for the Yahoo mailing list was, I think, the single nastiest thing which Dave Sim has ever written. The commentary takes the form of a heavily moderated Q & A session. Someone implies that they think that Dave regards Cerebus' 'gospel' as a genuine addition to scripture. Sim responds:

'Also, nice try from the he/she/it side of the fence: slipping an accusation of blasphemy against me in under the fence. Obviously I don’t think 289-290 is divinely inspired.....Yes, I know you didn’t mean to accuse me of blasphemy, but that’s the nature of atheists. You’re empty vessels wide open for demonic possession 24/7.'

Someone else asks a rather geeky question about the dates of Cerebus' world and how they relate to real history. Sim's answer is that it's a mistake to assume that Cerebus' story is taking place on our earth. But it comes out as:

'My assumption is that everywhere in the universe planets roughly the size of YHWH all enact their various tantrums and plodding resistance to the truth and infantile he/she/itisms in roughly the same way (and for all I know bigger planets are no different in the same way that all he/she/its are the same), so Cerebus’ story could probably have been enacted on any of a trillion times a trillion little blue balls that think they’re God just as there are probably a trillion times a trillion of each of you everywhere in the universe all behaving exactly as you do, each of whom has chosen to turn his/her back on God. Or maybe out of the trillion times a trillions versions of you there might be one or two that are actually God-fearing, but that would surprise me if it was true.'

So: Sim is no longer the only Real Man in Canada or the only man on Earth who is not a feminist: he is now possibly the only God-fearing man in the universe.

A question about the politics of Cerebus' world leads to a rant about terrorism:

'In order to sustain itself as a political movement, he/she/itism in our society needs to convince people that the proper reaction to killing Islamist Muslims who are plotting violence against civilians is grief at their death and/or fear of the people killing them. The proper reaction isn’t grief and/or fear. The proper reaction is relief coupled with determination to kill as many more as it takes until Freedom is the universal condition of man.'

Note the straw doll. Who are these liberals who express grief when Islamist Muslims who are plotting violence against civilians are killed? What Dave has in mind is liberals who express grief when innocent Muslim civilians are caught in the cross fire; or else liberals like myself who are concerned when individuals who may or may not be plotting violence are arrested, imprisoned or killed without having been given a fair chance to defend themselves. If we could win the warren terra simply by shooting a few easily identifiable and clearly labeled Bad Muslims, then life would be much simpler. In Dave's world, you can, and it is.

And in passing:

'Guantanamo Bay doesn’t actually bother Democrats but they do see it as the way back into the White House (mistakenly, in my view).'

We then get on to theology. Apparently, you can still be tempted to sin after you are dead. In order to be on the safe side, when he gets to the Afterlife Dave will do nothing but recite his prayer until the Day of Judgment. He concludes:

'I think unconsciously I was documenting the loss of my soul which was pretty much a given until I started reading the Bible. It’s one of the reasons that concepts like “fun” really don’t resonate with me at all anymore. My only interest at this point is Not Blowing It Big Time and making it to the grave and Judgment Day without any serious slip-ups. Like allowing people to accuse me of blasphemy without refuting the charge. I am on high alert 24/7 for exactly those sorts of things. '

Now I can think of a lot of words to describe this writing. 'Fanatical' and 'Puritanical' come to mind. It's the kind of Bad Religion which sees life as an inconvenient distraction you have to get through in order to reach heaven, with all pleasures and human interaction being temptations which are best shunned. But it doesn't have any of the joy of the Lord or the sense of being part of a positive, self-assured community which can make both puritanism and fundamentalism very positive forces in some people's lives. I might also describe the writing as 'mean spirited' or 'just plain nasty'. But mad? The product of mental illness? I think this lets him off the hook too easily.

I still don't quite know what follows from any of this.

* I say 'alleged' because there is a widely disseminated tradition that he behaves as a perfect gentleman towards his girlfriends, and is quite charming towards any other women he happens to bump into.

Thursday, August 31, 2006

When Pants Ignite

Every time that people talk about "creating the characters," I always say I co-created them. I co-created Spider-Man with Steve Ditko. I co-created The Fantastic Four and the Hulk with Kirby. I co-created Iron Man with Don Heck. Very often, when people would write about us in the newspapers or the trades, they would say, "Stan Lee – Creator of Spider-Man," and that would get Ditko angry – but I had nothing to do with that! I have no control over what journalists write.

Stan Lee, interviewed on IGN, June 2000

Celebrating his 65th years at Marvel, Stan "The Man" Lee comes face-to-face with some of his greatest creations of all time. Five all new 10 page stories by Stan Lee with 10-page backup tales from top talents in the industry, along with reprints of classic Stan Lee stories. Stan Lee Meets Spider-Man. Stan Lee Meets Dr. Strange. Stan Lee Meets The Thing. Stan Lee Meets Dr Doom. Stan Lee Meets The Silver Surfer.

Marvel comics flyer, September 2006.

(Stan Lee's name appears 17 times in this leaflet. A no-prize for anyone who guesses the number of occurrences of the words "Ditko", "Kirby", "Jack", "Steve". The cover for the Spider-Man comic appears to be have been copied from Ditko's art on Amazing Fantasy #15, and the cover for the Thing appears to have been copied from Kirby's art on Fantastic Four #51.)

Wednesday, August 30, 2006

A.N W.I.L.S.O.N I.S A S.H.I.T

Davewatch

Friday, August 25, 2006

Thursday, August 24, 2006

Walking With Jesuses

Exorcists traditionally used spells and rituals to evoke the power of God: Jesus simply told evil spirits to go away, as if he personally had authority over them. But the only person who has authority over Satan is God. It is very significant that the Gadarene swine ran into the sea, because Leviathan is a symbol of the devil, Leviathan lives in the sea, and in the Old Testament, YHWH is sometimes depicted overcoming Leviathan. (Er...nice try.)

When a crippled man was brought to him, instead of healing him, Jesus announced that his sins were forgiven – something which only God can do. Omar implies that in saying this, he is pointing out (or possibly deciphering) a previously neglected significance. In fact, the meaning of the story is absolutely explicit in the text of Mark's Gospel.'Why doth this man thus speak blasphemies? Who can forgive sins but God only?'

On another occasion, Jesus calmed a storm on the sea of Galilee. He seemed to be giving orders to the elements – which everyone knew was God's job. Indeed, one of the Psalms specifically talks about God controlling a storm. (We aren't told which Psalm, because that might make us switch over to Emmerdale instead.) But there was no need to do any deciphering to discover this, because it is quite explicit in the synoptic account. 'Who can this man be? Even the wind and the waves obey him!'

Finally, the disciples are shocked (in the film, if not in the Bible) when he changes his mind and heals the gentiles daughter; because Jesus appears to be unilaterally extending the privileges of the chosen people to a goy – which surely is God's prerogative. Omar goes so far as to say that Jesus himself is surprised by this; a pretty weak point, since Jesus has on several occasions argued from the Old Testament that God is concerned with non-Jews.

Monday, August 21, 2006

Tuesday, August 15, 2006

Silver Age Jesus

I just came across a 1955 Superman story called 'The Girl Who Didn't Believe in Superman'.

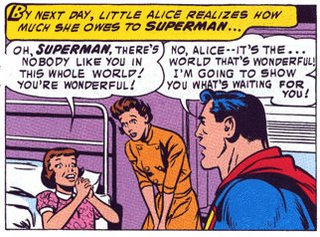

I just came across a 1955 Superman story called 'The Girl Who Didn't Believe in Superman'. I think I first read it in a British Superman Annual when I was a kid. I can't think why I, a devout Marvelite, allowed such a book into my bedroom. Re-reading it makes me wonder if there is after all a precedent for identifying the Last Son of Krypton with the Son of God.

The Daily Planet is organizing it's annual 'Lovely Child' photo competition. The prize is a round-the-world sightseeing tour with Superman: but the winner of the competition, little Alice Norton, turns out to be blind. Not only that -- but she doesn't believe that there is any such person as Superman. The Man of Steel uses his super deus ex machina power to become an accomplished eye-surgeon and performs an operation which restores Alice's sight. She realizes that Superman is real after all, and he takes her on the promised world tour. Because of the publicity, Alice's long-lost father turns up: he's been in hiding because he blames himself for the road accident which blinded her. His wife reveals that he wasn't really to blame. Superman has not only restored her eyesight and her joie de vivre, but also Alice's family.

The splash-page for the episode shows Superman dragging a truck through the street on a chain to demonstrate his super-strength. Alice stands to one side saying "It's all a trick. There is no such person as Superman." This idea is elaborated in the first section of the story: Superman demonstrates his various powers to Alice, but she provides a rational explanation for each of them. (For example, when he uses his telescopic vision to tell her what her mother is doing she replies, not unreasonably, that it's common knowledge that she works as a child-minder in the afternoons.)

This is a modern take on the old story about the blind men and the elephant. It amusingly shows how someone's beliefs about the world are determined by their point of view. It is also a classic Superman puzzle story. The young reader is supposed to be amused by the ingenuity of Alice's rationalizations, and to wrack his brain to think of a super-stunt that she can't explain away. (Much of the 1950s was spent pitting Superman against deliberately un-super opponents. "How can I convince a blind girl that I am Superman?" is really the same kind of question as "How can I trick Mr. Mxyzptlk into pronouncing his name backwards?") The resolution to the puzzle – that Superman's X-Ray vision accidentally reveals the cause of Alice's blindness – is actually a bit of a cop-out. But it takes the story off in a new and much more interesting direction.

Alice's real problem is not her blindness: it's that she is caught up in a post-modernist paradox. She thinks that Superman is "a myth, make believe, a modern fairy tale." She tells the Man of Steel that "No man could have super-powers like that! Superman is just make believe...like the fairy tales Mommy tells me!" But from our point of view, that is precisely what Superman is: a modern fairy tale. The imaginary Superman-free world that Alice has created for herself is the same as ordinary world which we readers live in every day. Alice's mother say that "she retreats from reality more and more each day" – even though for us, it's believing in Superman, not doubting him, that would be considered a retreat from reality.

Alan Moore's classic 1986 story "Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow" began with the brilliant line "This is an Imaginary Story. Aren't they all?" I think that Bill Finger had made the same joke 30 years previously.

Alice's physical blindness is a metaphor for her inability to perceive the innate goodness in the world. According to her mother "Because of her blindness, Alice has become a bitter, cynical child!" This cynicism is explicitly connected to her disbelief in Superman. "She must be drawn out of her shell! She must be made to believe in life again! If I can make Alice believe in me, she might begin to believe in the world around her...in the pleasure even a blind child can have! That's why it's so important that I convince her there is a Superman!" It's her skepticism, not her disability, which is the problem: if she believed in Superman then she could enjoy life – even if she remained blind.

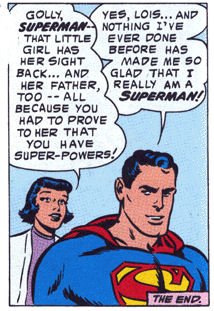

Having restored her sight, Superman flies Alice around the world. This is not depicted merely in terms of a person who has suffered a temporary loss of vision enjoying their restored faculties: we are supposed to imagine someone seeing the world for the first time – indeed, discovering for the first time what kind of world they live in. "This is your country" says Superman. "Golly! I never realized America was so big!" she replies. The word "wonder" is used four times in this sequence: Alice says that Superman is wonderful for having healed her; Superman says that it is the world itself that is wonderful. And Alice, who a few pages before was being cynical about fairy tales, suddenly decides that the whole world is like children's fantasy and she is a character in it. "It's just like you said it was...wonderful! Alice in wonderland, that's me!" Bet you didn't spot that line coming. The restoration of Alice's physical sight is a metaphor for the restoration of her "sense of wonder".

What does the story 'mean'? In 1955, comics were written by adults and read by children. (Today, they are written by fanboys and read by no-one.) The comic may be playing with the idea that adults who lose their childlike enjoyment of fantasy also stop enjoying real life. It may simply be a warning to its readers not to lose their sense of wonder. It may even be telling them, very gently, that although they will one day grow up and realize that there is no Superman, the world is still very wonderful without him. At the beginning of the story, Alice's rejection of Superman is a rejection of the world itself. When she recovers her vision, she wants to give all her attention to Superman, but he points away from himself, and toward the world. In the penultimate frame, Alice has literally turned her back on Superman, because her attention is directed to her happy family. Superman slips away without saying goodbye, leaving Alice, in a very positive sense, back in a world without Superman. "Come on" he says to Lois "They don't need us any more." The Alice of the splash page ("there's no such person as Superman") and the Alice of the last page ("they don't need us anymore") could be seen as negative and positive metaphors for growing-up.

But when I read a story about faith, which involves the healing of a blind person, I am inclined to ask whether the story is "really" about Jesus. In the Bible, Jesus heals several blind people; indeed, he begins his mission by announcing "freedom to the captives and recovery of sight to the blind." The New Testament healing stories are just that – stories about supernatural cures. But Christians also read them as metaphors about spiritual healing and forgiveness. "I once was lost, but now am found, was blind, but now I see." For a Christian, to come to believe in Jesus is to have your eyes opened; to see the world in a new way. Can this possibly have been in Bill Finger's mind when he depicted a little girl healing her life by believing in Superman?

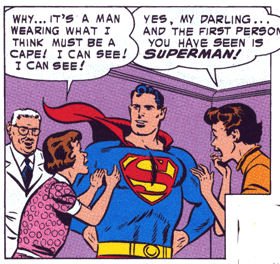

The scene in which Alice is healed is worth a close look. Superman can instantly memorize the contents of an entire medical library and uses his X-Ray vision and super-speed to perform an operation which no earthly surgeon could ever do. (This raises a question -- why doesn't he use his knowledge and power to heal all the other blind children in the world? – which some people have also wanted to ask about God.) The actual surgery isn't shown: all the drama is saved for the day when the patients bandages are removed. I don't know what post-operative dressings look like in a real hospital, but here, they look exactly like a blindfold: as powerful a way of illustrating "recovery of sight" as you could imagine. The whole sequence has a Biblical whiff. The captions drift into archaic language "Slowly, the binding cloth..." (why not just "bandage") "is unwound" (not "removed" or "taken off")"and light falls upon Alice's staring eyes!" Alice only gradually works out that what she is looking at is the Man of Steel. "Something...tall...it's getting clearer...why...it's a man wearing what I think must be a cape! I can see! I can see!" Bill Finger has temporarily forgotten that she was only blinded four years ago and knows perfectly well what a cape looks like. The metaphor about "seeing the world for the first time" has temporarily overridden the literal story about a child with a fragment of a windshield in her optic nerve. Does this recall the Biblical story of the blind man who said "I see men as trees, walking."? Many a preacher has pointed out that the first person that the blind man saw was Jesus: Alice's mother exclaims that the first person her daughter sees is Superman. In the next frame, Alice adopts what is distinctly an attitude of prayer to thank her saviour. Her words to Superman seem a bit prayer-like as well "Oh Superman! There's no-one like you in the whole world!"

The final incident in the story is also worth a glance. (Didn't they cram a lot of story into 10 pages in the 50s?) It seems that Alice's father disappeared after the road accident which originally blinded her. "I couldn't look at my little girl's sightless eyes without knowing that I was responsible because I was driving the car!" In fact the crash was caused by a mechanical fault for which he was not to blame. He's been "running away needlessly from his own conscience!" It would be over-subtle to see this as an allusion to the disciples' question to Jesus about the blind man in John's Gospel ("Rabbi, who sinned, this man or his parents, that he was born blind?") But it is very, very striking that Superman's actions have not only cured Alice of her blindness, but also cured her father – who is called John, by the way -- of his guilt. It goes without saying that for Christians, the important thing about Jesus wasn't that he cured sick people, but that he told them that their sins were forgiven. Alice's father is briefly suspected of wanting to steal the money which generous Daily Planet readers have donated to help Alice and her mother. This also represents a change in how Alice sees the world "I never realized people were so good."

For anyone who grew up with Stan Lee's melodramatic over-writing, this 1950s Superman is astonishingly simplistic; even naive. There is hardly one word of what you could call dialogue in the whole story: everyone talks in pure exposition and the "Alice in Wonderland" line made me cringe with embarrassment even when I was 10. However, like many superficially naive children's stories, it actually has considerable complexity and emotional depth. We have a character whose literal darkness is the outward representation of an inner darkness – she has no father, her mother is poor,she thinks that there is nothing nice about the world -- all summed up in her disbelief in Superman. Superman heals her, restores her inner light, her family, and makes her see things she never saw before – the beauty of America, the inherent goodness of the human race.

Any relationship between Superman and Jesus is one of resemblance rather than symbolism: Superman, the character, does some of the same kinds of things which Jesus did, with some of the same kinds of results. This seems to me to be more sophisticated and effective than the approach of the movies, which do little more than point up certain supposed similarities between the origin of Superman and religious saviour myths. I think that the religious language that is used in the "healing" scene makes it more than likely that Finger was aware of the overtones of his story. But maybe a half-remembered Sunday School lesson just worked its way onto the page while he was writing against a deadline.

Any relationship between Superman and Jesus is one of resemblance rather than symbolism: Superman, the character, does some of the same kinds of things which Jesus did, with some of the same kinds of results. This seems to me to be more sophisticated and effective than the approach of the movies, which do little more than point up certain supposed similarities between the origin of Superman and religious saviour myths. I think that the religious language that is used in the "healing" scene makes it more than likely that Finger was aware of the overtones of his story. But maybe a half-remembered Sunday School lesson just worked its way onto the page while he was writing against a deadline.

Andrew Rilstone is a writer and critic from Bristol, England.

If you have enjoyed this essay, please consider supporting Andrew on Patreon.

if you do not want to commit to paying on a monthly basis, please consider leaving a tip via Ko-Fi.

The Girl Who Didn't Believe in Superman was written by Bill Finger and drawn by Wayne Boring and Stan Kaye. Superman is copyright DC comics. All quotes and illustrations are used for the purpose of criticism under the principle of fair dealing and fair use, and remain the property of the copywriter holder.

Please do not feed the troll.

Friday, August 11, 2006

Do you remember when cars treated "stop" lights as an instruction, rather than a suggestion?

Yes, I have heard of Childline. They are the ones who hang around shopping malls, hassling people and trying to sell them credit cards.

Do you remember when the only people you ever saw cycling on the pavement were on tricycles?

Yes, I have heard of the WWF; but personally, I think it's all staged. And even if it isn't, I still don't want a credit card.

Do you remember when cyclists tried to avoid pedestrians, as opposed to swearing loudly at pedestrians who don't avoid them?

Last week it was extinct animals, this week it was abused kiddies, next week it will be save the kangaroo, but I still will not want one of your damn credit cards.

I asked a policeman what side of the pavement cyclists are supposed to cycle on, and whether they had to obey traffic lights or not, and he said "Mind how you go, Sir."

"Free broadband forever." The "free" part means "twenty pounds a month" and the "forever" part means "you will wait forever for us to connect you."

There are some stretches of pavement where you don't have to dodge cyclists. These are the stretches occupied by parked cars.

Has anyone ever actually managed to buy a Megabus ticket from Bristol to London for £1?

Or the stretches of pavement occupied by the 143 new kinds of wheelie bin the council has issued us with.

Ticket reservation is compulsory on this service; but if you try to sit in the seat you have reserved, then the person sitting in it will turn up his I-Pod and threaten to knife you.

It said "Haircut for £6" so I said "A couple of inches off all round, leave it over my collar and ears, and brush it forward." He said "That will be £10 in your case." I said "All right, how much will you cut off for £6"

Would you like to donate to Mencap? Do I look mad?

Yes, thank you, as a matter of fact I do have 20p for a cup of coffee. (But if you tell me where you can get a cup of coffee for 20p, I'll give you a quid. Boom boom.)

Would you like to donate to Amensty? Not if you attached electrodes to my genitals.

A female attendant is on duty in this toilet.

Would you like to donate to the RSPCA? La-la-la-I'm-not-listening.

Run of out petrol? No money in your wallet? Need £5 for a taxi. Yes; that seems to happen to people a lot on this street; although I must admit that the mobile phone call to your wife was a nice touch.

The cashier in Tescos chased me down the aisle and out of the shop because I had forgotten my pot of jam; but no one ever mentions it when someone is unexpectedly helpful.

But seriously; would anyone mind if I punched a charity collector on the nose?

.jpeg)