Turning Point, Featuring the Return of Dr. Octopus!

Villain:

Doctor Octopus

Supporting Cast:

Betty Brant, Bennet Brant, Blackie Gaxton, Aunt May,

+ a Prison Governor and a chorus of crooks and cops.

First appearance:

Spider-Man’s Spider-Tracers.

Observations:

This is only the second issue which J. Jonah Jameson has not appeared in.

Most of the story, which is about Betty trying to help her brother, takes place in Philedelphia, “the city of brotherly love”.

Spins a web, any size: Web is used to block a doorway, blackout a searchlight, and as a bandage for a sprained ankle.

Marvel Time: Doctor Octopus has served 9 months in jail. His original sentence must have been around 310 days.

Failure to communicate: On page 6, Bennet visits his client “in jail”, and Blackie talks about being sprung “from jail”. But on page 9, Spider-Man soliloquizes that “Octopus is sure to try to spring Blackie while he’s still a prisoner in the courthouse. If he waits til they take him to the state pen, it will be a much tougher job.” In fact, the building is clearly shown as a castle-like prison with many barred windows. Lee spots that it Doc Ock gets Blackie out far too easily, but his retro-fit doesn’t match the illustrations.

Medieval moralists said that Fortune was like a huge wheel. As long as you were going up, you were fine: but once you reached the top, there was nowhere to go but down. Aristotle said that tragedy involved one particular moment when everything appeared to be going great for the hero and suddenly everything started to go wrong. This catastrophic change was known as a perepiteia : a turning point.

Amazing Spider-Man #11 is not so much a turning point as a staying the same forever point.

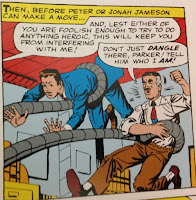

As usual, The Writer and The Artist can’t quite agree on what the Selling Point of the issue should be. The cover shows us a rather stiff Dr Octopus fighting an equally un-dynamic Spider-Man, with the words "The Return of Doctor Octopus" in big white-on-red letters. But there’s a fifty word caption — I would guess the longest that has ever appeared on a cover — asking "What happens when Spider-Man decides to reveal his identity to someone else?" The interior splash page answers the question — rather daringly — by taking us right to the end of the story, and posing a new question: "How did it happen, and why?"

This is really not a bad compromise, and it is going to stay in place for most of the year. The covers — the outward facing images — will show Spider-Man confronting a villain, with Stan Lee congratulating himself on dreaming up such a impressive adversary. ("We’ve created the greatest villain of all for ol’Spidey!" "Wow just wait til you see the Green Goblin!" "So you think there are no new types of villain for ol’Spidey to battle, eh?"). The internal splash page — directed at people who have, after all, already bought the comic — will promote the actual storyline, asking a question like "has Spider-Man really turned to crime?" (no) "has Spider-Man really gone mad?" (no) or "has Spider-Man really lost his powers?" (no).

Or, this time: "Why has Betty decided that, like her boss, she hates Spider-Man. For ever and ever?"

It doesn’t seem likely that either Lee or Ditko ever planned out a plot arc in advance. Background characters are fleshed out and become major supporting players, changes of direction are back-filled by Stan Lee. When Lee introduced nasty Mr Jameson in issue #1, he didn’t know he was going to become more-or-less the co-star of the comic, and certainly didn’t know that Spider-Man was going to fall in love with his secretary. But it was a canny move. Peter might have carried on dreaming about Liz and having fights with Flash over her: but that would have been obvious and boring. The idea that he has a close romantic friendship with a slightly older career gal is much less predictable and far more interesting.

In Amazing Spider-Man #2, J. Jonah Jameson’s secretary briefly appears, but we don’t find out her name. Issue #4 marks the first appearance of "Miss Brant". In issue #5, Miss Brant tactfully tells her boss that he is too obsessed with Spider-Man and at that precise moment Peter Parker notices how pretty she is. Stan back fills the story, giving the impression that Peter Parker and Betty Brant have know each other for some time ("I never realized how pretty Betty Brant was!" "I never realized how I felt about her!”) In fact, they have barely exchanged twenty words. In issue #6 Peter tries to ask her out but is interrupted by J.J.J. Finally, in issue # 7, the two of them end up flirting behind Jameson’s desk after Spider-Man and the Vulture have trashed the office.

Their relationship isn’t classic romance comic fodder. Betty really gets on with Peter and Peter really gets on with her. We never see them on a date; but we do see them sitting together in the dark while Aunt May is having major surgery. "Maybe I haven't got many friends!" says Peter "But one wonderful one like Betty makes up for all I haven't got!" It’s one of the most believable relationships in comic books.

People married young in those days — so aren’t we running headlong towards a obvious conclusion: fire burning in the hearth and spider-babies on the rug? When Stan Lee thought he was writing a realistic convention-breaking graphic novel, that might have happened. But that idea is long buried. Spider-Man is a super-hero with a secret identity and a utility belt and an arch enemy. His comic now has a clear formula — a brilliant formula, a formula that allows for endless elaborations, but a formula nonetheless. There will always be a new villain, Aunt May will always be at death's door. Peter will always be dropping into the Bugle and Betty will always be waiting for him there. If he unmasks, gets married, leaves home — even, god forbid, gets a proper job or gets drafted into the army — Amazing Spider-Man as we know it comes to an end.

So something has to happen to make it impossible for Spider-Man to unmask: to freeze Peter and Betty in a permanent impasse. Turning Point is an obligatory piece of plot machinery. At some point in the future, Flash Thompson is going to have to find out who Spider-Man really is: but that moment can be infinitely delayed. But the longer Peter goes without telling Betty the truth, the worse a cad he appears to be. When he thinks (in issue #7) "Betty can’t care for me if she won’t confide in me!" he comes across as a shocking hypocrite.

In issue #9, Betty is upset because Peter goes to photograph the prison riot after she had asked him not to. She speaks calmly to Peter and tries to explain her feelings. "Peter, I never told you why I left high school last year and took a job! I never told you about someone I once knew — who reminded me of you! But I don’t want to be hurt again!" Peter responds angrily "I get the message! I’m not Mr Perfect!" But a page later he is claiming that it was how Betty who "flared up" at him, and Betty is the one doing the apologizing.

In issue #10, Betty is bullied by the Enforcers. Although she tells Peter that it is a case of mistaken identity, she confides to the reader that she has "foolishly borrowed money to a loan shark!" It can’t have been very much — she has paid off the principal on her secretarial wage — but the Big Man has doubled the interest. She decides to leave town, because she doesn’t want Peter to know how silly she has been and certainly doesn’t want him to risk his life protecting her from the Thieve's Guild.

Two different secrets have been foreshadowed. A mysterious person in Betty’s past, strongly implied to be dead, who is somewhat like Peter and who worked in some dangerous occupation; and a foolish attempt to borrow money at high interest rates. If Steve knows where he is going with this, he doesn’t tell Stan, who trails issue #11 as "Spider-Man discovers the strange secret of Betty Brant…!"

It's not particularly strange. It seems that Betty's brother, Bennet Brant, is a lawyer who is either working for the mob, or has run up a huge gambling debt, or both. A gangster named Blackie Glaxon has agreed to cancel the debt if he, Bennet, springs him, Blackie, from prison, which Bennet facilitates by, er, arranging for Betty to drive Doctor Octopus from New York to Philadelphia.

Up to now, it has always been fairly plausible chains of events which have caused the two halves of Peter’s world to come crashing together: a science demonstration going wrong at his school; a criminal robbing his place of work. Betty’s involvement with the Enforcers was already a step too far, but this crosses a line. I could suspend my disbelief in a schoolboy who clings to walls and fights giant talking lizards; but when Spider-Man spotted Betty driving Doctor Octopus’s car I found myself thinking "No, I just can’t accept that."

Why is Betty driving the car, anyway? Even granted that crazy scientists with metal arms are the only people who can break through prison bars (and I can't help thinking an acetylene torch would have done the job just as well); why do you need to incriminate your sister to get him there? Doc Ock is a free man. He could have caught the bus.

It is possible to square "I gave Bennet all the money I had so that he could pay his debts to Blackie" with "I borrowed money from a shark". It is quite hard to square "I ran away to Philadelphia because I didn't want Peter to get involved with the Enforcers" with "I ran away to Philadelphia because I didn't want Peter to know I have a dishonest brother". But it's much harder to square "I don’t want you to be a photographer because I once had a friend who enjoyed danger" with "I don’t want you to be a photographer because I am still at this moment trying to help my crooked brother.” And very hard indeed to think that a gal would ever refer to her brother as "someone I once knew".

Very conveniently, Betty drops a map of Philadelphia as she is getting into the car, so Spider-Man knows roughly where she is going. Even more conveniently, he has just invented a wonderful new plot device: a "detailed model of a live spider" which "sends coded messages" which he can "pick up with a small portable receiver." This is, of course, the prototype spider-tracer. The next time it appears it will be an "electrically treated spider-pin". It’s actually fairly pointless. If Spider-Man had simply followed Betty to Philly, swung around the city for a few panels, and then spotted her, I don’t think anyone would have complained. It’s the sort of coincidence which happens a lot: Spider-Man always swings past the exact person he most needs to find. And the new electronic spider-plot device is still coincidence-powered. The second time Spider-Man needs to track down Betty he remarks "A good job they used the car which had my gizmo on it!" Yes. A good job indeed.

Doc Ock springs Blackie from jail, but Blackie breaks his promise to Bennet and ends up taking him and Betty hostages, and Spider-Man comes along and there’s a big gun fight, and…

Somewhere, buried deeply in Peter Parker — so deeply that he never mentions it or thinks about it — is an overwhelming guilt that he caused the death of his beloved Uncle because he did not act. But today, Betty Brant’s beloved brother dies because Spider-Man did act. (I have often wondered if Bennet's friends called him "Ben" as well.) He dies "like a man" trying to protect his sister, but if Spider-Man had not been there, he might very well have survived. Betty’s initial reaction mirrors Peter’s reaction in Amazing Fantasy #15: "(He) is dead..because of Spider-Man!” (Spider-Man tells Gaxon "There’s no place on earth you can hide from me!" which is exactly what he said to the uncle-slaying burglar.)

Stan Lee piles the irony on as only he can "I hate you Spider-Man .. If only Peter were here!" cries Betty. Oh what a tangled web we weave...! When Betty has calmed down, she modifies her accusation, instead damning Spider-Man with the most terrible kind of faint praise. "It wasn’t his fault! He was trying to help us!". And she replaces her hatred of Spider-Man with something worse: an irrational revulsion. The girl who didn’t want Peter Parker to take photos because it reminded her that her brother had a gambling debt (or something) announces "I still never want to see Spider-Man again! I couldn’t bear being reminded…of Bennet!" Her hatred of Spider-Man is irrational. Like J. Jonah Jameson, she is an arachnophobe.

Guilt is not a helpful emotion. If you act, sometimes, good people may die. If you do not act, sometimes, good people may also die. It’s an unjust world and virtue is victorious only in theatrical performances. But Peter Parker will increasingly come to feel that the deck is stacked and the universe hates him personally.

The final three panels are as good as anything Ditko ever drew and (once again) as good as anything Lee ever wrote. Note the big candle in the foreground: is the scene taking place in a funeral home, or at a wake? Peter can’t now tell Betty who he is, and he is trapped in another lie, albeit a very white one. “Of course I understand! And I’m sure Spider-Man would too, if he knew!”

If he knew. Peter Parker destroys his relationship with Betty Brant there and then and he must know that is what he is doing. Can you imagine, four or five years hence, Spider-Man unmasking to the girl he loves and her saying "You stood there — hours after my brother had been shot — literally over his dead body — and you lied to me?"

One month and three panels later, Betty will be back in New York; working for Mr. Jameson again. She has a new haircut — which covers up her ear-rings — a new style of clothes (rather stylish purple) and a new handbag. She’s lost her whacky eyebrows. But this is the end for Betty Brant as a character. The new Betty is little more than a girl-shaped golden snitch for Doctor Octopus to bait his spider-trap with.

The final frame of the comic has a tiny figure of Peter Parker walking away from us. It’s an image we’ve seen several times before. But instead of the the split face motif, a giant figure of Spider-Man is walking in front of Peter Parker. I am sure this panel must have suggested the iconic Spider-Man #50 cover to John Romita.

It makes me wonder. Did Steve Ditko originally envisage entirely different words in those speech bubbles? Was Peter Parker originally going to say, not "I understand why you hate Spider-Man" but "I understand why you are staying in Philadelphia". So the

perepiteia would have been Betty leaving the story altogether, clearing the way for a relationship with Liz Allen (who becomes unexpectedly a Peter Parker fan in the very next episode.) But Lee overruled him, leaving Betty as a lose cog in the story engine, a relic of a previous story-line, a dangling plot threat which can never be tied up.

*

Later continuity reveals that Bennet Brant did not die from the gunshot, but survived to become the Crime Master. Later continuity can fuck off.

A Close Reading of the First Great Graphic Novel in American Literature

by

Andrew Rilstone

Andrew Rilstone is a writer and critic from Bristol, England. This essay forms part of his critical study of Stan Lee and Steve Ditko's original Spider-Man comic book. If you have enjoyed this essay, please consider supporting Andrew on Patreon. if you do not want to commit to paying on a monthly basis, please consider leaving a tip via Ko-Fi.

Pledge £1 for each essay.

Leave a one-off tip

Amazing Spider-Man was written and drawn by Stan Lee and Steve Ditko and is copyright Marvel Comics. All quotes and illustrations are use for the purpose of criticism under the principle of fair dealing and fair use, and remain the property of the copywriter holder.

Please do not feed the troll.

.jpeg)